Physician and psychiatrist; originator of antabuse, who switched to apomorphine and led an investigation into its efficacy.

Information on Martensen Larsen’s life, his achievements and set backs, will be available shortly.

Nils Draebye was born in Denmark in 1941. He graduated as a Master of Science Pharm. from the Danish Pharmaceutical University in Copenhagen in 1973. Aged 32 he joined Axeltorvs Pharmacy in Helsingør, as senior pharmacist.

Nils was involved in the manufacture of apomorphine tablets and capsules for Oluf Martensen Larsen from 1973 until he left Axeltorvs Pharmacy in 1980 to become a production manager for the pharmaceutical company Northern Drug & Chemicals Ltd. In 1986, he worked as chief pharmacist at the University Hospital Pharmacy in Odense before returning to Helsingør in 1991 as the new owner of Axeltorvs Pharmacy. His friendship with Martensen Larsen continued until the doctor’s death in 2000. Nils retired from Axeltorvs Pharmacy in 2008.

Axeltorvs Pharmacy in the 1970s

I came to Axeltorvs Pharmacy in 1973. Working with Torben Skjot Jorgensen, the owner of the pharmacy, was special. He was unlike other pharmacy owners. We didn’t just sell pharmaceutical products but also made them in our own laboratory. He encouraged both experimentation and innovation and his staff supported him. Physicians heard about this and encouraged Torben to develop their ideas for new treatments. Other pharmacies in the local community didn’t always approve of what we were doing.

All new treatments produced at our pharmacy complied with the then regulations, enabling us to produce extemporaneous drugs, i.e. drugs in small quantities not recorded in the Nordic Pharmacopoeia or by a drug company.

Axeltorvs Pharmacy consisted of more than 45 employees (pharmacists and technicians). I was the manager of a team of five pharmacists. Torben would bring in clients who wanted to develop new pharmaceutical products; he asked my advice on whether their proposals were possible. Developing new products in small scale along with various physicians was an activity we did in our spare time because it interested us professionally. It was not financially attractive to make extemporaneous medicine.

Oluf Martensen Larsen and apomorphine

Oluf Martensen Larsen first came to the pharmacy in 1972. He wanted to develop an alternative treatment to Antabuse® (Disulfiram). He thought aversion therapy against alcoholism was flawed and was searching for an alternative pharmacological treatment for addiction.

He asked Torben to help him improve the effectiveness of apomorphine in a tablet formulation. He wanted to develop an oral dose medication that the patient could self-administer. Traditionally, the standard treatment required a physician or a nurse to inject the apormorphine.

Oluf sought the advice of specialists such as Jørgen Scheel–Krüger, Arvid Carlsson and Lock Halvorsen to see if a new formulation of apomorphine was possible. Their knowledge helped him to devise the dispensing of apomorphine as tablets instead of an injection. He prescribed the medication extemporaneously where the composition of the apomorphine tablet was written down in detail.

Normally, it takes about 10-15 years to bring a new drug to market but by using an extemporaneous prescription Oluf could develop a new method to dispense apomorphine. Many pharmacists didn’t like this form of prescription because making lesser amounts of drugs and at the same time checking the right composition of the ingredients was time consuming and expensive for the pharmacies. Before Oluf contacted Axeltorvs Pharmacy, he had already been to pharmacies in Copenhagen to see if they would help him but was rejected. He approached us because he lived a few kilometres along the coast from Helsingør. This resulted in an agreement with our pharmacy, since we had the knowledge both to produce tablets and capsules in large and lesser amounts. Torben and I were excited by the opportunities the project could give us at the pharmacy. Torben also liked and trusted Oluf and we all became very good friends.

The first time I met Oluf I discovered quickly that he as a psychiatrist was different from other physicians I knew and worked with. Social commitment of the patients was the primary goal for him, while making money played a minor role.

He didn’t tell me about his involvement in the development of Antabuse® (Disulfiram). As a student, I had been taught by Professor Erik Jacobsen knew he was one of the founders of Antabuse®. I didn’t know Oluf had worked so closely with them and thus had extensive experience with the use and effect of Antabuse®.

Oluf told me he found the dopamine agonist apomorphine better than Antabuse®. Male alcoholic patients told him it was often difficult to get an erection but it happened easily with apomorphine. I didn’t believe him when he told me that apomorphine could be used to help erectile dysfunction. Later I realised he was right as the registration by Abbott in 2001, of the apomorphine tablet Uprima® 2 and 3 mg. for orodispersible use against erectile dysfunction occurred a year after Oluf’s death.

At that time physicians who treated alcoholics were not well regarded in the medical profession. Oluf would say anyone thinking of a medical career shouldn’t go into addiction. At that time, I didn’t give a thought to the status of his work. I was excited about the investigation into apomorphine and the opportunities I was given at the pharmacy.

Making apomorphine tablets and capsules

In the beginning Oluf asked us to make apomorphine tablets 5mg. for usage under the tongue. He believed the anastomosis under the tongue, in the oral cavity, would help the drug to be absorbed faster into the bloodstream and not degrade as quickly as it happens in the stomach when taken orally.

Apomorphine was known as an injection medicine and could only be administered to a patient by a professional. Our task was to prepare apomorphine in tablet form which the patient could easily self-administer.

Oluf asked us to try different doses of apomorphine. His intention was to prescribe medicine to suit each patient individually because each patient responds differently to a dose of apomorphine.

We combined the tablets with metoclopramide to limit their emetic effect. We managed to prepare tablets to be swallowed – by increasing the dose to between 20 mg and 50 mg – and that worked on the patient – though apomorphine degrades more rapidly in the stomach before it reaches the blood. Maybe 3-5 mg of the drug reaches in the bloodstream. This made their compliance uncertain.

When we were asked to make 100 tablets we would have to use a quantity of apomorphine to produce 300 tablets because there is a lot of wastage when producing machine made tablets. About 200 tablets worth of raw material remained in the tablet making apparatus when making 100 usable tablets. If we had an order for a much larger amount it made the process less expensive but Oluf didn’t always need or want a large amount. His order depended on the dose he wanted.

When Oluf requested 1000 tablets by phone they would be delivered to his clinic. The clinic then paid for his order. Sometimes he came into the pharmacy to collect them himself. For economic reasons, we usually ordered the apomorphine raw material in lesser amounts of a half to one kilo at a time. It lasted for about 3-6 months depending on how many patients Oluf had at the time.

One of the challenges working with apomorphine is its stability. If it’s exposed to light it turns a brown colour. The apomorphine would be delivered to us in a container with an air tight lid which we had to unscrew in a dark room. The first time I ordered apomorphine the people at the wholesaler processing the order, mistook it for a narcotic (!) due to the name similarity with morphine.

To make sure that the content of the tablets produced in large quantities was plus or minus 5% of the declared content, we sent samples for analysis at the DAK Laboratory (Danish Pharmaceutical Association Control Laboratory).

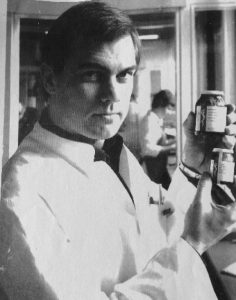

Photo by Marianne Grøndahl, 1975. Copyright 2017.

Oluf would experiment and try different doses of apomorphine. It seemed that some patients needed their own individualised dose for it to work. On many occasions, he would ask us to make a small number of tablets and as I have already referred to it wasn’t economic.

At the time I was teaching pharmacy students at the University how to make small amounts of hard gelatine capsules and had bought a capsule making apparatus for this purpose. It produced 100 capsules at a time. This is how we came to make apomorphine capsules for Oluf. Since these capsules were hand-made we could vary the amount of apomorphine in each batch. This made them more expensive than the tablets. But making the capsules made it easier for us to experiment with the apomorphine dose requested by Oluf. We also experimented using Levodopa and made capsules for the night called “night powders”.

Swallowing a tablet or capsule helped make the experience of taking apomorphine less unpleasant but there were difficulties associated with this method of administration. When producing a capsule it was necessary to increase the dose of apomorphine as once it is in the stomach it breaks down quickly losing some of its affect. It also takes longer to be absorbed into the blood stream. We added other compounds such as Metoclopramide to stop the vomiting effect and help with its absorption.

Sometimes Oluf phoned to tell us about a patient and the prescription he wanted them to have. Sometimes, when the patient collected their prescription they would tell us that the tablets or capsules didn’t work well for them. Occasionally, if we had their permission, we shared this information with Oluf. This approach of drug compliance was very unusual for a local pharmacy.

Visiting Arvid Carlsson

I didn’t know much about how apomorphine worked in the body. It was Oluf’s interest in the drug that made me curious and I began to investigate it myself. On one occasion, I went with him and Torben to Gothenborg to meet Arvid Carlsson, I remember Arvid organised for us to sleep in a clinic on small investigation beds to save money on our accommodation.

Arvid didn’t say much it was mostly Oluf who talked. I contributed with my knowledge within the pharmacology of apomorphine. We were all interested in the drug’s half-life (T½ = 33 minutes). Arvid didn’t really converse with me but he was kind and gave me a book on the processes and function of Dopamine in the brain. I still have the book on my shelves.

Oluf Martensen Larsen’s practice

Oluf saw private patients at his home and at his practice in Copenhagen. He and Lock Halvorsen were also assigned to a public Polyclinic in Copenhagen where they treated patients with our tablets. There, treatment was free and there was the opportunity to test apomorphine tablets with many patients.

Most alcoholics admitted to hospital wouldn’t be given the kind of individual attention Oluf could give. His approach was special and inclusive and he had many patients in his practice.

A reimbursement system operated in Denmark based on 50% reimbursement paid by the public health insurance. Then, the patient covered the expense for the other 50%. When Oluf made an extemporaneous prescription for apomorphine there was no reimbursement as the refund system only covered registered products. Some of Oluf’s patients paid for all their medication. Many couldn’t afford to pay for their treatment, and therefore sought financial help in the municipal social services. I believe Oluf occasionally paid if a patient couldn’t afford the treatment.

Helsingborg Sweden

Oluf also treated alcoholics at a public alcohol polyclinic in Helsingborg, Sweden. He went there by ferryboat from Helsingør.* A lot of Swedish alcoholics were sent to this polyclinic and Oluf persuaded the staff to try apomorphine on them. The Swedish chemists were not able to make the tablets or capsules so Oluf brought our tablets on the ferryboat to the clinic in Helsingborg. Swedish pharmacies at the time were state-run unlike Danish pharmacies, which were privately owned. This meant that the Swedish pharmacies couldn’t produce new treatments on a small scale like we could in Denmark. Their rules were stricter than ours. Torben knew the pharmacy managers in Helsingborg and with their assistance arranged for Swedish pharmacy students to have work experience at our pharmacy.

Getting to know Oluf and Visits abroad

In 1976, I accompanied Oluf and Torben on a visit to Hamburg to meet Dr. Hans Wilhelm Beil who used apomorphine injections in his clinic. We stayed with him and his family. We discussed Oluf’s use of apomorphine with alcoholics and gave him some of our tablets. We also reviewed a book he was preparing for publication about the recent investigations into apomorphine. I was also taken to Beil’s local pharmacy to educate the staff on how to produce apomorphine tablets.

In 1977, I attended a psychiatric medical conference in Prague (former Czechoslovakia) with Oluf and Torben. Oluf brought the staff from the alcohol polyclinic in Helsingborg; two young physicians and three nurses. Dr. Beil brought some of his physicians from West Germany as well.

Czechoslovakia was a communist country at that time. The authorities at the conference stated officially that they had practically no alcoholics in the country! It amused the delegates at the conference as the reason for us being at the conference was to discuss the treatment of alcoholics. It was a problem for the friendly Czech physicians who had invited us. They had many alcoholics in their practice and were not able to talk freely about their experiences.

I went along for the ride and to talk about the production of apomorphine tablets to other physicians and pharmacists. I was greeted by a woman who was a Commissioner of the Communist Party. She was more interested in hearing if apomorphine really had any effect than in understanding the tablet manufacturing process. It was still a very eventful trip for all of us – especially for socializing purposes.

New regulations affect availability of apomorphine

After Denmark joined the European Union in 1973 the regulations for producing drugs in local pharmacies changed.

Until 1975 the pharmacy structure in Denmark was based on the production and supply of drugs. Private pharmacies produced drugs listed in the Nordic Pharmacopoeia and extemporaneous drugs. These made up about 50% of the total output of the products while the registered drugs from pharmaceutical companies accounted for the other 50%. Pharmacy production in the local pharmacies decreased steadily up to 1975, when compositions of the Pharmacopoeia legally had to be registered.

The production of extemporaneous drugs in private pharmacies stopped around 1990. Two approved pharmacies were set up to manufacture extemporaneous drugs for all the private pharmacies in the country. Oluf could order his apomorphine tablets and capsules from them but at a much higher price compared to the cost of the tablets produced by Axeltorvs Pharmacy.

I left Axeltorvs Pharmacy in 1980 to work for the pharmaceutical company Northern Drug & Chemicals Ltd. Because of the new legislation Axeltorvs Pharmacy discontinued the production of tablets in 1982. The laboratory and production facilities were closed. The small quantities of handmade tablets and capsules Oluf wanted became very expensive to make. This was of course a problem for him and his patients.

In 1986, I became chief pharmacist at the University Hospital Pharmacy in Odense. In 1991, I returned to Helsingør as the new owner of Axeltorvs Pharmacy. I continued the collaboration with Oluf until his death in 2000.

Strangely, after he died a number of doctors contacted me asking if they could get apomorphine for their alcoholic patients. A few even asked if they could prescribe Uprima for this purpose! I suggested they contact one of the approved pharmacies and use a magistral prescription if they wanted to give their patients apomorphine.

I often visited Oluf to get a cup of coffee and discuss daily life. He had his house in Hellebæk by the sea a few kilometres along the coast from Helsingør. Here he lived with his partner Bente who was a social worker. He had a great personality and it was always pleasant and interesting to be in his company. Sometimes I attended a dinner party with him, Torben and our wives. Oluf always drank milk for dinner while we drank beer or wine.

Working for Oluf and Torben at Axeltorvs Pharmacy benefited my career. I learnt how important it is to be service-minded, progressive and to take tough decisions and not be dismissive of new proposals and ideas.

Nils Draebye

Snekkersten, Denmark June 2017.

*Helsingør is in Denmark across the Øresund Strait from Helsingborg. The ferry takes 20 minutes between the two ports.

My Father Oluf Martensen-Larsen

by Annette Martensen-Larsen

My grandfather Martensen-Larsen was a pastor. My father, Oluf, had three older brothers. The eldest was in the police. There was another in forestry, the third was a clergyman. All of them were in high positions and they were rather formal. My father, who became a psychiatrist, was the youngest and unconventional. He was a new kind of person compared to his older brothers. Untraditional.

When he was a young doctor, during the German occupation, he was connected to the resistance movement. He vaccinated members of the resistance movement hiding in the forest, against typhus.

My father inherited a large wonderful house in Hellebaek from his mother’s sister. She was wealthy and a member of parliament. Before he inherited he had a large plot of land behind his aunt’s house, with three modest house on it. He lived in one of them until he inherited the big house.

For years and years on Wednesdays he stayed at home and he would sort out little cards, with statistics, this was preparation for his book, which he wrote when he was almost 80.

He was a modest man and didn’t spend much money on himself. He spent money on his house and his garden. He didn’t care about dressing up but he had nice clothes.

He would take a glass of red wine later in his life. He couldn’t take white wine because he got a headache. He thought red wine was good for his health. I remember he liked Cointreau.

I was not aware of the significance of my father’s contribution to addiction. I remember, when I was child, my father had patients living in a special house. Up to ten people living in a villa where they were taken care of for the “cure”. They were given Antabuse. I went there with him. He had many patients in the Antabuse periods in Sweden. Then my father went from Antabuse to Apomorphine. He thought Antabuse was not so good to take and Apomorphine was better.

He earned a lot of money from the Antabuse and provided a good foundation for the family. We were prosperous and lived in a bungalow in Hørsholm with a very nice garden.

My father was a committed psychiatrist and his working day was about sixteen hours. He came back late in the evening. He was a calm man and somewhat taciturn. But he could get excited with the subjects he was dealing with. He had humour and was charismatic and a good listener. When he explained something he was interesting.

My mother admired his work and she followed his career with great interest. Sadly, my mother and father separated when I was an adult. She then became a respected Colonel in the Danish Air Force.

I worked for him in his clinic for a couple of years in the 1970s. He asked me to help him out, after his fine secretary, who was Jewish, left him because of illness.

My father didn’t just treat alcoholics then. He saw all kinds of nervous people. He kept them out of hospital. He was equally interested in medicine and psychology. He was a scientist in both disciplines.

His practice was in the centre of Copenhagen, near the Tivoli Gardens. He had two rooms. One was a large waiting room where his patients were received by his secretary and offered tea. My father’s room was next door. It was large with old furniture and comfortable. He had a big desk, which was tidy and he had pictures on the wall, some were of his family.

When I was helping him he saw patients on a Tuesdays and Thursdays. On the Wednesday he worked at home, in the country, Hellebaek, (30 km North from Copenhagen). He saw patients there as well. There was a large garden to the house which he gardened. I imagine the patients told him dreadful stories and he got rid of these by gardening.

He tried to solve the problems of addicts. I never heard him being sad about anybody. The patient would have told him about their problems. He (was) good at listening. But he would speak out on what to do with their problems. Some of his patients were actors and actresses. He kept them off alcohol and helped them to keep performing. His patients were grateful. He kept them going and was beloved by them.

He used Apomorphine for his patients. A pharmacy in Helsingør made them and my father decided their chemistry.

My father talked to me about his good results with Apomorphine. When he explained his work, he got excited and I felt his charisma. I remember hearing about Arvid Carlsson. He drove to Sweden to see him. He worked with another doctor, Lock Halvorsen, who also used Apomorphine. He was also in correspondence with some German counterparts. He met them and invited them to Hellebaek.

He concentrated on his work and did it as well as he could. He didn’t think about training younger doctors, of anyone inheriting his work. A kind doctor, who was the same age as my father, took in some of his patients. My father thought he would live to be a 113 and treated patients until his death aged 87.

Annette’s memories recorded and transcribed by Antonia Rubinstein, February, 2016.

Søren Buus Jensen recalls as a newly qualified doctor how he came to test apomorphine for Martensen Larsen in 1974.

Interview available January 2018.