Irish born doctor, medical researcher and author, who discovered small regular doses of apomorphine reduced craving.

Francis Hare, an iconoclastic doctor whose life spanned more than 70 years, 2 continents and 3 major areas of study, is a forgotten pioneer in the history of medicine. Not only was he one of the earliest to investigate and formulate treatments and theories about the emergence of allergies, but his approach was one of the earliest examples of the systematic use of evidence-based medicine to transform the lives of patients.

Little is known of Hare’s early life other than that he was born in Dublin in 1856. He attended Fettes College in Edinburgh, a new school opened in 1870 to fund the education of boys who had experienced a family misfortune. (1)

Hare went onto study medicine in London, first at St Thomas’s Hospital and then at St Mary’s Hospital, finally receiving his medical degree from Durham University in 1884. A year later he took up a post as the assistant resident surgeon at the Brisbane General Hospital, in Queensland, Australia. (2)

Brisbane in the 1880s was a “hotbed of typhoid” (3) and Hare was put in charge of the over-crowded fever wards. There he was confronted by the near-total failure of the doctors to control or treat the condition; an accepted method was to administer brandy or whisky and hope. The mortality rate was high and, spurred to action, Hare set about finding a way to help patients that worked.

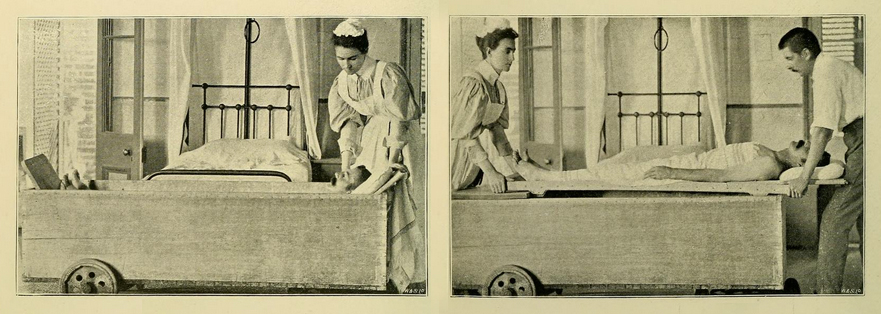

The method he found was a Swiss technique known as the “Cold Bath” treatment. It involved soaking the patient in cold water to reduce their temperature, which Hare believed was the main source of danger for the patient. What sets Hare apart, however, is that he ran a trial to see if the approach worked or not. The trial confirmed his hunch, convincing those at the hospital, and the treatment was adopted. This combination of intellectual curiosity and rigor was to become a hallmark of his approach to medicine. (4)

In 1891, aged 35, Hare was appointed Chief Medical Superintendent of a new hospital in Charters Towers, a rapidly expanding mining town 1,300 km north of Brisbane.

The town was plagued by recurrent fevers and sickness, and his intense desire to find out how and why this was, resulted in the earliest descriptions of dengue haemorrhagic fever and the conditions that led to it. His formal report of his findings was so well-regarded it is still referred to this day. (5-8)

After returning to Brisbane in 1897 Hare published ‘The Cold Bath Treatment of Typhoid Fever.’ (9) This, along with his rigorous work on mosquito-borne fevers, established him as a leading authority on the treatment of typhoid, spreading the technique across Australia.

Hare’s medical career was taking off. As well as writing up his ideas on health, diet and disease he saw private patients and in 1900 was appointed Inspector General of Hospitals for Queensland. However, the position was short lived. An economic recession saw state funded salaries slashed and Hare resigned to take on the post of chief superintendent of The Diamantina Hospital for Chronic Diseases in Brisbane. (10)

The Diamantina opened in 1901. It had 72 beds and a ward for consumptives, then an incurable disease. Hare set about improving sanitation and ventilation, installing gas lighting, running water and a septic tank. Wards had access to hot water, a bath and a lavatory. Recognising the need for specialist nursing care, he helped establish a new training school for nurses in Brisbane. (11)

In 1904, not long married and perhaps wanting to start a family in healthier surroundings, Hare and his young wife left for England. He was 48. Back in London Hare wasted no time promoting his expertise as a hospital director and author on medical matters. In 1905 two new books authored by him were published, ‘The Food Factor in Health and Disease’ and ‘A Common Humoral Factor of Disease and its bearing on the practise of medicine.’

In the well received, ‘The Food Factor in Health and Disease’, (12) Hare was one of the first doctors to suggest that unexplained chronic complaints might be caused by diet and surroundings, and to attempt to place such a suggestion in the realm of science rather than the pre-scientific medical notions of “miasmas”. (13) In his introduction to ‘A Common Humoral Factor of Disease’, he wrote that he would “take a deductive view of disease”, applying the same logical and empirical rigor to analysing allergies as he took to helping sufferers of typhoid. (14)

It wasn’t long before Hare found a position suitable for a man of his talents and experience. The recently formed Norwood Sanatorium needed a Chief Superintendent to oversee its move to Beckenham Place, a large mansion within commuting distance of the City of London.

Owned by the respected philanthropist Joseph Rowntree, the enterprise was run by a committee of specialists, many of whom were members of the Society for the Study of Inebriety. Their ambition was to establish a centre of best practice that would raise the medical status of the study and treatment of alcoholism. (15)

Hare, with his experience of managing hospitals, researching the cause of diseases, developing effective treatments and disseminating good practice was well placed to turn the treatment of addiction into a legitimate area of medical interest.

Set in 200 acres of parkland, Beckenham Place had its own farm and a large market garden. There was outdoor entertainment: a tennis court, bowls and a croquet lawn. The Norwood Sanatorium opened with 13 “guests”, each paying the then-hefty sum of £750 a week for full board and treatment. Hare had brought with him more than just Australian experiences; he had the words “No Worries” inscribed over the front door. (16)

Hare took the view that alcoholism was a disease and not a moral failing. He believed the alcoholic could be cured if they voluntarily accepted treatment and demonstrated a determination to give up alcohol for good. The most suitable environment for tackling the disease was in a sanatorium away from the distractions of home and work. (17)

Unlike other practitioners working with alcoholics Hare maintained that denying a patient alcohol at the start of their treatment was dangerous and cruel, and likely to cause delirium tremens (18). He gradually weaned patients off alcohol while giving them a regulated diet and a combination of different tried and tested chemicals, such as hyoscine hydrobromide, strychnine nitrate and atrophine sulphate to help manage the physical and mental difficulties a patient would suffer as they were treated. However, one particular medicine he used had a quite extraordinary effect; apomorphine (19).

Hare may have first read about the use of apomorphine as a calming agent for delirium tremens in a 1900 edition of The Lancet. (20) The report described its use by Charles Douglas, a Boston based doctor, who had been using it to calm his patients and send them to sleep. However, Hare’s use of “the most useful single drug in the therapeutics of inebriety” (21) went far beyond a simple symptomatic treatment of distressed patients.

While his use was partly like that of Douglas, in that he would give it as a calming agent to distressed patients to send them to sleep, he noticed that it had subtle yet powerful effects beyond causing vomiting and sleep.

It seemed to change the very mindset of the patient; not only would it make them feel calmer, less anxious, with more clarity of mind, but it also seemed to reduce the patient’s craving for alcohol. This led to him adopting a procedure of giving small doses of the drug over several days to help patients through the difficult early stages of withdrawal. (22)

Hare being Hare, he didn’t just give it and hope for the best; he took detailed records of his patients. Of the 390 patients that he kept records of, 62.3% were still full abstainers when followed up between 6 months and 2 years after their admission. (23)

This combination of success, rigor and the prestige of the institution led to Hare becoming an authority on alcoholism in the UK, and he was asked to write the entry on ‘Alcoholism’ for the Medical Practitioners Encyclopaedia” in 1915, then the leading reference for the medical profession. His positive feelings about the drug are clear;

Here, fortunately we have in apomorphine a drug which accurately it’s all such emergencies. Indeed, it is not too much to say that without the assistance of apomorphine it would be impossible to carry on with any satisfaction a free sanatorium into which were frequently admitted acute cases of alcoholism. (24)

Despite the first world war, activity at the Norwood Sanatorium flourished with a constant flow of patients. Hare, an active council member of the Society for the Study of Inebriety, hosted a visit in 1917 for society’s members to observe the sanatorium at work. (25)

By the 1920s Hare’s health was in decline, and in 1925, aged 69, he retired from the Sanatorium. Over the following three years he focused his energies on revising his 1912 book, ‘On Alcoholism’, but died before finishing it of a stroke in December 1928. He was 72. ‘The Alcohol Habit and Its Treatment’, completed by Walter Masters, a colleague from the Sanatorium was published in 1931. (26) In its introduction by Sir William Wilcox, a past president of the Society for the Study of Inebriety’ Hare is referred to as “one of the greatest authorities in this country on the subject (of alcoholism). Apomorphine was singled out as a “most valuable drug in the treatment of certain phases of the alcohol habit“ … “deserving of further investigation.” (27)

Despite Wilcox’s recommendation, Hare’s revolutionary use of apomorphine as a treatment for craving itself, rather than just as an emetic and calming drug, would not be taken up by the medical profession. This was compounded by the increasing irrelevance of the sanatorium model of treatment; few could afford the expensive and intense treatment regimes.

In a cruel twist of fate, apomorphine would become associated with a different type of treatment for alcoholism; as an agent purely to induce violent and unpleasant vomiting in “aversion therapy”. It took until the 1950s for his more humane and effective use of the drug would be acknowledged. In many ways a sad ending for a man who did so much to help establish the very earliest seeds of evidence-based medicine, and who made so many important contributions to so many different areas of medicine. He married fierce intellectual interest with a deep concern for the wellbeing of his patients, and shared his results as far as he could.

References

- British Medical Journal 1928 Dec 29. 2 (357):1200. Death Announcement of Dr.F.E.Hare.

- Ibid.

- The Brisbane Courier 20.05.1929. Obituary for Francis Everard Washington Hare.

- Ibid.

- ADF Health September 2003 – Volume 4 Number 2, Infectious diseases, Dengue, Major John G Aaskov, BSc, PhD, FASM, FRCPath, RAAMC.

- Hare FE. The 1897 epidemic of dengue in North Queensland. Australas Med Gaz 1898; 17: 98-107.

- A Re-Examination of the History of Etiologic Confusion between Dengue and Chikungunya, Goro Kuno 11. 12, 2015.

- Dengue Fever C. Armstrong Public Health Reports (1896-1970) Vol. 38, No. 31 (Aug. 3, 1923), pp. 1750-1784.

- The Cold Bath Treatment, F.E. Hare. MD. Macmillan and Co 1898.

- The Brisbane Courier 20.05.1929. Obituary for Francis Everard Washington Hare.

- ‘The Diam’. A History of the Diamantina Hospital, Dr R.F.J. Ward 1982.

- Hare, Frances Washington Everard. The Food Factor in Disease, Vol I/II, Longmans, Green & Co, London, 1905.

- Another Person’s Poison: A History of Food Allergy, Matthew Smith, 2015.

- Hare, Frances Washington Everard. A Common Humoral Factor of Disease and Its Bearing on the Practise of Medicine, Longmans, Green & Co, New York, 1905.

- The Norwood Sanatorium, A Prospectus. Publisher, S.H.Benson, 1905.

- History of Beckenham Place Park, Friends of Beckenham Place Park website.

http://www.beckenhamplaceparkfriends.org.uk/history.html, - Hare, F.E The Sanatorium Treatment Of Inebriety, British Journal of Inebriety, 1908, Vol 6, Issue 1.

- Ibid.

- Hare, F.E. ‘On Alcoholism, It’s Clinical Aspects and Treatment,’ J.&A. Churchill, 1912.

- Apomorphine As A Hypnotic, The Lancet, April 14. 1900. P. 1083.

- Hare, F.E. ‘On Alcoholism, It’s Clinical Aspects and Treatment,’ J.&A. Churchill, 1912.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Practitioners Encyclopaedia of Medical Treatment. Edited by Langdon Brown and Keog Murphy. 1915.

- Berridge, V. ‘The Society for the Study of Addiction 1884-1988’, British Journal of Addiction Vol 85, No 8, Aug 1990.

- Masters, W. (1931). The alcohol habit and its treatment. London: H.K. Lewis & Co.

- Ibid.

Illustrations

- The Cold Bath Treatment, F.E. Hare. MD. Macmillan & Co 1898.

- Staff at the Charters Towers Hospital, Queensland, 1896.

Apomorphine’s unique property published in 1915

When he wakes, the patient’s mental case is entirely altered.

He may be sober, he is at least quiet and tractable, and moreover, he is free for the time being from any craving for alcohol.

The craving may return, however, and then it is necessary to repeat the injection, it may be several times at intervals of a few hours.

These succeeding injections should be quite small, 3 – 6 min being sufficient. Doses of this size are rarely emetic.

Francis Hare, ‘Alcoholism’ The Practitioners Encyclopaedia of Medical Treatment, 1915.