Arvid Carlsson

Arvid Carlsson, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2000 for showing that dopamine is a neurotransmitter, was interviewed in 2013 by Antonia Rubinstein about the use of apomorphine to treat alcoholism. He discusses why the drug, which he views as having been effective, did not make it into the modern era as a treatment.[1]

Note: Text in brackets has been added with the permission of Professor Arvid Carlsson.

AR: When did you first start to investigate apomorphine?

AC: My major interest in apomorphine goes back when it was discovered by a Dutch pharmacologist, called Ernst, that apomorphine is an agonist on dopamine receptors.

Dopamine receptors (were) my main interest at that time. I had moved to Göteborg in the early 1960s and I was the referee on Ernst’s paper[2], who, based on very sound pharmacological observations, concluded that this drug acts on dopamine receptors. (This is when) I became interested in apomorphine.

Can you tell me something about dopamine and its connection with alcohol?

I was involved in an experiment in the department of pharmacology – the results were published. We went to four parties in our lunch room, in the evening. What we were dealing with was a double-blind study, where we twice out of those four times took alphamethatyrosene which is an inhibitor of dopamine synthesis. We took it every four hours – maybe every six hours, maybe four doses over a 24 hour day. We (also) took (a) placebo and we then got together and had our party and there were some sober observers. We took about 20 centilitres of Danish Aqua Vita – a good brandy, called Snapps (and) the outcome was very clear. It showed that we could very easily distinguish between those evenings when we had (the) drug and those who had the placebo. When we took the first drink (the party) sounded normal and you felt something good, but after a while it sort of faded away and you (got) rather sleepy. A number of the people in the department went from the room to find a place where they could like down. It was no fun at all. (The results) were very clear and (were) published.

Before (this experiment) we gave rats alcohol. We measured something related to dopamine – probably the rate of dopamine synthesis in the brain and found it was stimulated. We also found that the rat was stimulated along with some behaviour and biochemistry they came together. We could block that by means of an inhibitor of the synthesis of alphamethatyrosene. That was the background for our human experiment. We were much involved in the reward system and the effect of drugs on the reward system – abuse drugs.

With your awareness of apomorphine for treating alcoholics did you not use apomorphine?

We didn’t do that. At that time, we had some hope about α-Methyl Metatyrosine – but of course not just with connection of abuse but also in connection with psychosis that was our major interest. The alcohol was a little bit by the side so to speak, that in the sixties (we) in the Department of Pharmacology here in the University of Göthenburg. We put together a team where there were not only pharmacologists but also medicinal chemists who could synthesise molecules and the molecule we started out from in this programme was apomorphine.

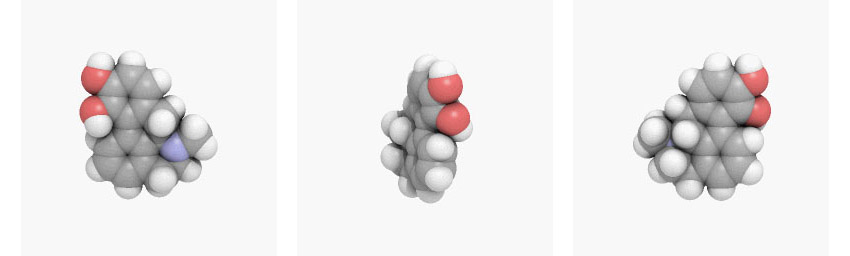

We formulated the goal simply that we would like to have a molecule that would not be an emetic first of all and it would have better pharmacokinetic properties because apomorphine is a bad drug from that point of view. (It is) very short acting. So, we started out from that molecule and we took it a little bit apart. It is a complicated structure with all these rings. So, we took away one ring with the others, from the point of view of chemistry to have something in-between dopamine and apomorphine. But we also wanted to get rid of a catechol because catechol is a terrible thing to have from the point of view of pharmacokinetics. So, we soon had one hydroxide molecule. It was simplified apomorphine with just one OH group in the 3 position which is the most powerful position. So therefore, we came across a number of drugs – very interesting drugs. And actually, we have continued along that line and the drug, we are (currently) experimenting on (is) OSU6162.[3] That is along this (string). If you put them on a row you can see that it goes from here to here to here. So, they are all related. So, in a way this compound is what I would say that would be a molecule that would be most suitable for testing the original apomorphine hypothesis.

I don’t doubt at all that apomorphine worked. But I’m not surprised that it didn’t live that long I don’t know if it’s used any more at all. I mean it would be as an emetic then.

Why do you think apomorphine has an association with being an emetic?

Simply that it is one of the areas where you have many dopamine D2 receptors. In the area postrema, which is in the medulla longata, that is an emetic centre. And the drug like dopamine cannot reach those receptors. So, if you give dopamine you are not going to vomit but, if you make the molecule a little more fat soluble then you can get through the blood brain barrier and then you have this problem.

(If you use apomorphine) for injection that is a very different story. If you inject (apomorphine) you have much more activity. It’s a powerful compound.

If you knew of someone back in the 1960s who was suffering from a drink problem what treatment or doctor did you recommend?

Well in the Göteborg area there was a rather famous alcohol doctor his second name was the same as mine – Carlsson*. He might have been interested in apomorphine. So, I probably might have said, “Go to Carlsson” because he was an experimental kind of person.

Apparently patients who received apomorphine in capsule form, the oral treatment, didn’t feel sick. They didn’t have the desire to drink.

That makes a lot of sense. Because you probably have to consider the different receptors we have and low doses of apomorphine are doing more-o-less the opposite of what high doses are doing and that can be most readily demonstrated in rodents because they don’t vomit. They don’t have that problem. So therefore, if you measure the activity, psycho-motor activity of a rat in a new environment, where if you put a normal rat in a new environment it will start to explore and (be) rather active and then activity falls down over a number of hours when the rat has looked at everything and found out there is nothing more of interest. But if you pre-treat (the rat) with apomorphine you induce sedation. They are much less active, and they abstain from exploration if you give low doses. But if then you increase the dose of apomorphine – then it is going up and then finally it reaches a level that is above the normal level. I would suppose that the dose range where alcohol takes away the craving for alcohol – that would be the lower dose – where the apomorphine is an inhibitory. The reason why it is inhibitory is that certain dopamine receptors that are especially sensitive to agonist – dopamine itself, apomorphine and so forth they are located on the dopamine receptor on the dopaminergic neurons themselves.

So, it is like why are the dopamine receptors on the dopaminergic neurons? Well that’s for – it’s a feedback system. If the neuron puts out too much dopamine these receptors will be stimulated and tell the neuron this is too much and it’s going down and (with) apomorphine, if you give low doses, it will bind preferentially to those receptors so therefore you get an inhibition of the dopamine system and that I think is the reason why it can be useful to diminish the craving for alcohol.

Do you think apomorphine is habit forming?

That is something I feel doubtful about. If that has even really been demonstrated.

Why do you think apomorphine is sometimes linked to the word “danger”?

If you are very unlucky (and) you give apomorphine, and you have like, like other hypotensive drugs described in the old days when you had these very narrow telephone boxes and if you stand in there and you take a drug that makes the blood pressure fall and you cannot fall down then you can die that’s for sure. Low blood pressure if you cannot lie down that’s dangerous.

The literature that I read in pharmacological text books or internal medicine or neurology or psychiatry – one can read there about the side effects of apomorphine and they are well known. Of course, what is especially described – if you give – (it to) Parkinson patients – if you give it every day, to get rid of the downs, that you have between the doses of L-Dopa – then you inject it subcutaneously –then you can have changes in the sub cutis so (there) can (be) all kinds of formations that are not pleasant at all maybe even there could be some damage to the skin. That is known. Another thing that is described when you give it in continuous injection infusion into the sub cutis – (there) can be rather higher liability for mental disturbances all kinds of psychosis all kinds of psychotogenic activities showing. That is how it is described. I mean that is nothing. I haven’t seen any warnings that it can be dangerous.

Have you heard of any Parkinson’s sufferers who have been alcoholics?

That’s very rare to have alcoholics who have Parkinson’s. I think there are some, but they may not be true Parkinson’s. Because you need dopamine in order to become euphoric.

Could apomorphine be used for any addiction?

No, it’s pharmacokinetics are so poor. In order to be useful in addiction it should be available as an oral treatment.

Can you explain what you mean by pharmacokinetics?

(If) you take the drug as a pill (and) you measure the blood level (and how) quickly it goes up and how quickly does it come down. If you have something that is absorbed readily but at the same time metabolized very quickly you’ll have a short sharp short duration of action. And if it’s too short it’s not useful. In addiction you have the problem, throughout the day, when you are awake. You should have an action that should remain throughout the day. You would have to give apomorphine repeatedly.

Do you think apomorphine treatment for addiction has been superseded?

Yes. You see all the people in the drug field they are thinking very strongly in terms of pharmacokinetics. In other words, if you have a very short half-life of the drug like apomorphine they – I think mostly the pharmacokinetics aspects are over emphasised because people in pharmacology, or in the drug field, they don’t appreciate that many drugs, including abuse or the opposite, whatever, they have actions that outlast the presence of the drug. So that’s a very difficult thing to demonstrate, many times difficult to demonstrate – even though it’s not impossible at all. But, but to have, I mean, if you – if you try to have a comeback for apomorphine you will have enormous problems.

Can you explain why?

I think probably the pharmacokinetics. There are different aspects to pharmacokinetics. I didn’t mention that in addition to the question how quick (it) goes up and how quick (it) comes down it’s also how much of what you take is absorbed and if it’s a small amount that is getting through the gut and the liver then you have variations. So therefore, for the doctor to prescribe a pill is a terrible problem because the ability of people to metabolise a drug and therefore to utilize a drug has an enormous variation. So therefore, it’s not practical.

Doctors who have used apomorphine in the past such as Beil and Martensen Larsen write about trying to work out the dosages for each patient[4]. Understanding the correct dosage occupied Martensen Larsen thinking.

That’s correct. (The dose) has to be individualised. And so therefore if you have other drugs that (do) not have this problem why bother.

You (also) have the whole problem of marketing why should a drug company market apomorphine for this purpose? It wouldn’t make any profit from it. It is not patented. It cannot be patented. It has problems with variable dosage. If you market the drug you have to give (it) a description, you have to tell them the dosage should be such and such – and there are tremendous variations if only a small proportion of the patients fit in with this particular thing. It wouldn’t be worthwhile from the point of view of a drug company.

Finally, do you think that apomorphine might work for other addictions such as opiate addiction?

Yes. Dopamine is a reward system…, it is very centrally located – strategically located in the reward system and the reward system is of course involved in all kinds of addiction. It makes sense that if you have something working on alcohol. If it works via dampening the system, it is likely to do the same for gambling we know for sure. And we know of course from experience in Parkinson patients – that’s one of their problems they start to become gamblers of course. Because L-Dopa itself has very poor pharmacokinetics. That’s one of the problems you have these ups and downs that hit the system in a very unhealthy way, so you disturb very subtle long term regulatory mechanisms. They are called plasticity of the brain. That’s a major problem. So, you can have all kinds of problems. And, of course the long-term problems with Parkinson’s are due to these poor pharmacokinetics. The long-term problems with are a number of years Parkinson’s patients starts not to benefit that much any mo(re)… they get these fluctuations and all these problems.

Professor Carlsson, thank you for helping me to understand why, in your view, the use of apomorphine to treat addiction has not been adopted.

References

- Transcript of Rubinstein, A. Interview with Carlsson A. 30.05.2013.

Reproduced by kind permission of Professor Carlsson. - Relation between the action of dopamine and apomorphine and their O-methylated derivatives upon the CNS. Ernst AM. Psychopharmacologia. 1965 May 21;7(6):391-9.

- ‘One Step Closer to a new drug for alcohol dependence’. 14.10.15, Karolinska Institute.

- The Treatment of Multiple Drug Dependence and Alcoholism with Apomorphine.

Zusammengestellt und herausgegeben von Hanswilhelm Beil, Hamburg 1976. - GØtzsche, AL. The ‘sober-you-up’ drug, Doctor, November 18, 1976

- Carlsson, A to Rubinstein, A. Email correspondence, 10.7.11.